The Person Sitting Next to You: families all around us have incarcerated loved ones

That photo above is my tray table on a recent flight home from Vegas. Three homies recently out of prison and I were on our way home from the sixth annual Utah Wilderness Retreat.

It was another magical a week of learning how to fly fish, hiking down red rock slot canyons, trying cigars, pee-your-pants laughter, tears and healing conversation around the fire. As usual, all three gang-affected guys (Francisco, Jesus, Valentino) were recently released from prison and are part of Underground's growing community of healing.

Two of these guys I've worked with for over twelve years—in and out of addiction, new charges, prison letters, custody courts, prison again, job applications, medical fundraisers, all of it.

Remember Valentino with the heart medicine needed last year? That's him in the photo below in the black hat, alive and well. Thanks to many of you.

So to have both of them beside me in a trout stream, after all these years, talking late into the night and under the stars about our stories together, it felt like the promised land.

On this flight home, though, a woman sitting next to me seemed interested in all the photos from our retreat, which I was editing on my phone.

I told her about what we do at Underground.

Then she looked very tense. Jaw locked. No eye contact. Slow nods.

Assuming she wasn't warm to the idea of men getting out of prison, I told more stories: healing from the trauma they've experienced and caused, getting jobs, going to college, now raising kids, creating new lives in community, several of them now on staff with us.

I got on my soapbox about how mass incarceration has been a wildly expensive failure to our neighborhoods safe or whole.

She stared at me now, very serious.

"I'm . . . with you," she almost whispered. "I'm on your side."

"What do you mean?" I asked. Was this political code?

She looked cautiously around the seats in front of us, and behind us.

She then whispered again: she herself had been in prison before. Two years, a women's federal prison in CA.

This was a white woman, middle aged. Nice pedicure. Tan from her vacation. I had to check my own stereotypes of the formerly incarcerated.

I knew all the questions to ask next. This is what I do. Her story did not surprise me. It did, of course, break my heart.

When she was arrested for financial misdealings and taken to jail—in a college town just 15 minutes from where I live—everyone in her community ghosted her. All of them.

"Everyone my husband and I thought were our friends . . . just vanished," she told me, her eyes pooling up. "Overnight, we were dead to them."

This sudden abandonment was more painful than the loss of her job. More painful than the two years surviving in a federal lockdown facility, with its daily cruelties, and without a single visitor.

Her husband—sitting in the aisle seat beside her, who seemed very guarded—was her only support system, paying the bills on his own and the pricey prison phone calls for two years.

He had no friends to talk to about this lonely journey. What few relationships stuck around . . . didn't want to hear about it. Any of it.

Their collective shame was so thick, she told him to not bother visiting her in the CA prison during those years.

Upon release, they had no one to celebrate, welcome her home, nor help them navigate the legal underworld of prison reentry into their own town.

Finding new banking was hard. New job applications were terrifying, and most did not respond for an interview. They learned to live a life of hiddenness, never being known.

"I learned to keep my time in prison very much a secret," she said between deep, troubled breaths. If she ever mentioned it to someone she considered a new friend, they stopped calling back.

Her fear made sense, risking this conversation. She repeatedly wiped her tears and mascara off her checks.

On this same flight I was planning on reading a chilling sociological study called "Every Second: The Impact of the Incarceration Crisis On American Families."

Click the link above. The website is beautiful.

Its key finding in 2018 was this: 1 in every 2 people in the United States has had an immediate family member incarcerated.

Yep, read that again.

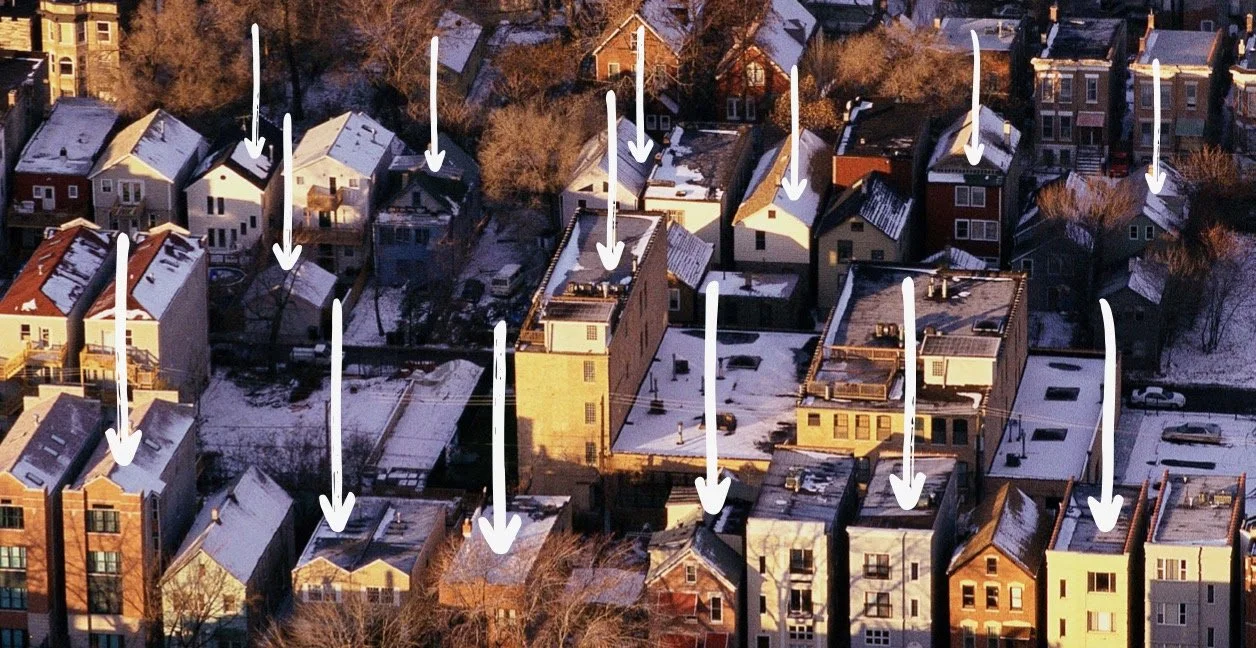

Nearly 2 million neighbors currently in cages today—those within mass incarceration's custody, seen as disposable "criminals"—these folks have families. Their families suffer in silence. Their spouses passing you in the grocery story. Kids in your kids' classes, getting picked up by grandparents after school.

Or, as we learned last week, maybe your pastor who's never risked telling the congregation about their sibling who was in prison for a decade, or the exhaustion of keeping secrets to protect the family.

They are everywhere.

They live on your block. If you go to a church, odds are these families are in your church. They might be sitting next to you on the airplane. They just don't tell you, or anyone.

That's how lockup culture—mass repression of wounds, secrets, and people—has been slowly killing all of us.

I told my new friend—let's call her Alison—sitting next to me on this tiny airplane, about how we at Underground do this weird thing: we help local communities, usually churches, learn how to love and walk alongside someone releasing from prison.

"Within weeks, they're all praying for someone and writing letters," I told Alison. "They aren't saints or specialists, but suddenly it's' normal to be talking about prison visits, collect calls, probation officers. Folks come out of the woodwork, or the pews, finally talking about their own run-ins with the law."

I told her we had three new teams getting started in her town this fall.

Would she want to meet some folks who wouldn't freak out about her time in prison, and be grateful to learn from her lived experience?

That's when she really wept. Alison gave me her info, to invite her to the next gathering.

Weeks later, one of those churches was getting ready to start One Parish One Prisoner. Pastor Jory was recruiting his team and emailed us:

"I've had some incredible experiences in showing one of the Underground website videos to congregants.

Two folks broke down crying because one person's child had previously been incarcerated . . . and another member's child is currently incarcerated. They had told no one in the congregation, including myself.

One person committed to joining the One Parish One Prisoner team."

This last weekend Alison, my friend from the flight home, courageously showed up to hear me preach at this new One Parish One Prisoner church, and sat down in the back pew, right there in her own town.

She heard my friend Rueben gush at the microphone about his journey out of prison with a team's helpand how confused he feels when his team keeps thanking him, for all the ways he's unlocked their fears and small worlds, helped them come out of hiding, and brought them joy, and closer to God. Together, they found an unexpected promised land in their own town.

(That's Rueben with his team, his friends, in the photos above.)

Alison saw all sorts of folks gathering at our table, signing up to create a friendship with someone else releasing to their town in a year.

She gave me a hug as she left and told me, almost regretting it, to add her to the team. "I'll be honest," she pointed at me. "This scares the shit out of me."

We are all learning how to walk each other home, how to open the locked doors, together.

Thanks for walking with us,

Chris Hoke

Founder & Executive Director, Underground Ministries